The oldest archaeological evidence in the territory of the current municipality of Vaglio Basilicata can be dated to the mid-sixth millennium BC. and come from the locality of Ciscarella.

The oldest archaeological evidence in the territory of the current municipality of Vaglio Basilicata can be dated to the mid-sixth millennium BC. and come from the locality of Ciscarella.

On the same site, the traces of ancient human settlements date back, however, to the Middle Bronze Age and reflect the belonging of the area to the most widespread cultures in the rest of the Peninsula.

In the period between the eighth and seventh centuries BC, as happens on most of the hills dominating the great Lucanian rivers, in Serra San Bernardo groups of shepherds, who practice subsistence agriculture, constitute a real village made by huts in pressed clay.

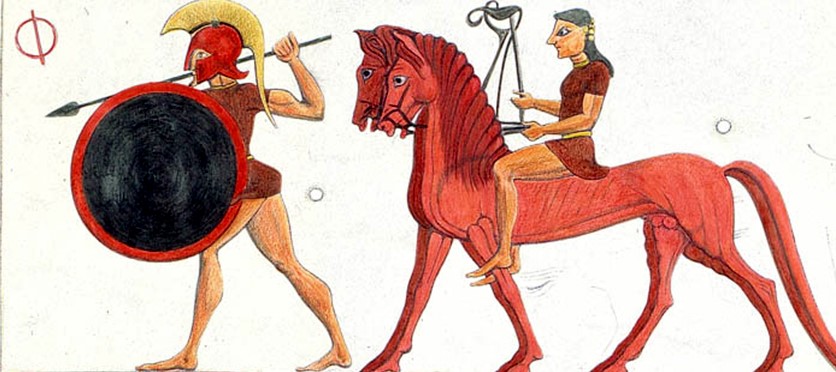

The cultural relationships determined by the foundation of the Greek colonies on the Ionian coast explain the presence of Etruscan-Campania bronze artefacts, ceramic vases and ivory and amber objects in contemporary funeral items found in Vaglio. In particular, the most recent excavations in Braida have brought to light the remains of a very rich necropolis, which returns ceramics and weapons, such as helmets, shields and greaves of Corinthian origin, together with iron swords of Italic type. In Rossano, on the other hand, a federal sanctuary dedicated to Mefite, female divinity of the waters, was erected.

Archeology in Vaglio has bravely taken the most avant-garde initiatives, the "house of the pithoi" was the first example of experimental archeology in southern Italy.

This is the volumetric reconstruction of a house dating from the fifth century BC, within whose perimeter the complex stratigraphy of the site starting from the eighth century is visible. B.C.

The division of the rooms respects the Lucanian age reorganization, which includes an entrance compartment, a room with fireplace and frame and a storage room for four large containers of foodstuffs (pithoi).

In line with the most advanced conception of a territorial museum, which aims at the knowledge and enhancement of local resources, in August 2006 the "Museum of Ancient Lucanian People" was inaugurated in Vaglio. For educational purposes, the exhibition offers virtual and life-size reconstructions of the main archaeological contexts with faithful reproductions of materials, which increase the accessibility and usability of the cultural heritage.

Inserting itself in the regional museum system through a dense network of thematic links, the Museum of Vaglio integrates the route in the archaeological sites of Serra and Rossano, according to what is the current idea of "widespread museum".

Shrine of the goddess Mefite was an important place of worship which she saw in the second century BC. an imposing restructuring, linked to the Roman presence in the area, and remained active until the first half of the 1st century AD.

Shrine of the goddess Mefite was an important place of worship which she saw in the second century BC. an imposing restructuring, linked to the Roman presence in the area, and remained active until the first half of the 1st century AD.

The numerous inscriptions found in it testify to an extraordinary cultural osmosis, comparable to that which can be seen from the Lucanian funeral paintings of Paestum. In fact, the writing is often Greek, the language used is Oscan, the institutions mentioned are typically Roman, albeit with a strong Lucanian identity connotation.

In September 2007 the archaeological investigations resumed in the sanctuary of Rossano di Vaglio, by the Archaeological Superintendency of Basilicata, under the direction of Marcello Tagliente, and in collaboration with the School of Specialization in Archeology of Matera, with the coordination of prof. Emmanuele Curti; likewise an overall review of the materials of the Adamesteanu excavations was initiated, by prof. Massimo Osanna. The excavation project pursued two main objectives:

1) define, with greater punctuality, the different life stages of the complex;

2) verify the presence of structures referable to the oldest phase of life of the sanctuary between the IV and III century. a.C., so far only certified by ex-votos and registrations.

The excavation concerned in particular the area of the altar and the central paving, and the southern area affected by a series of environments.

The central plateau of the ancient greenhouse settlement is generally assimilated to an acropolis, the highest part of the Greek city. Between the end of the 6th and the beginning of the 5th century BC, in this area the organization of the urban space is roughly articulated along a main road, which runs east-west, paved with wide paving stones and intersected by narrow perpendicular streets, on the which the houses overlook. In this area, in the mid-sixties of the last century, an imposing excavation was carried out to bring the walls of the houses to light. The huge heaps thus composed were subsequently removed by recovering numerous architectural terracotta, which allowed a better understanding of the building techniques used on the site. In particular, the antefixes made it possible to hypothesize a heavy roof covering, capable of supporting them, as seen in the experimental reconstruction of the house of the pithoi, at least for the phase datable to the fourth century BC. Previously the buildings had a rectangular plan with few internal divisions and a dry perimeter wall which included an uncovered courtyard, together with the covered areas. There were also buildings north and south of the road axis, not necessarily oriented with it, and traces of craft activities were found in the common open spaces. The archaic settlement was destroyed by large fires and from the first half of the IV, up to the first twenty-five years of the III century BC, there was an overcrowding of buildings on the acropolis and an intensive re-use of the discovered spaces, partially invading also the road axis central for the construction of new structures and creating a complex canalization system.

The central plateau of the ancient greenhouse settlement is generally assimilated to an acropolis, the highest part of the Greek city. Between the end of the 6th and the beginning of the 5th century BC, in this area the organization of the urban space is roughly articulated along a main road, which runs east-west, paved with wide paving stones and intersected by narrow perpendicular streets, on the which the houses overlook. In this area, in the mid-sixties of the last century, an imposing excavation was carried out to bring the walls of the houses to light. The huge heaps thus composed were subsequently removed by recovering numerous architectural terracotta, which allowed a better understanding of the building techniques used on the site. In particular, the antefixes made it possible to hypothesize a heavy roof covering, capable of supporting them, as seen in the experimental reconstruction of the house of the pithoi, at least for the phase datable to the fourth century BC. Previously the buildings had a rectangular plan with few internal divisions and a dry perimeter wall which included an uncovered courtyard, together with the covered areas. There were also buildings north and south of the road axis, not necessarily oriented with it, and traces of craft activities were found in the common open spaces. The archaic settlement was destroyed by large fires and from the first half of the IV, up to the first twenty-five years of the III century BC, there was an overcrowding of buildings on the acropolis and an intensive re-use of the discovered spaces, partially invading also the road axis central for the construction of new structures and creating a complex canalization system.

The city walls, built during the Lucanian occupation phase of the site, or in the mid-4th century BC, run about 2.5 km long, following the contour lines, on at least three sides of the mountain. It consists of two parallel curtains, interspersed with a filling of earth, stones and landfills. The external facing is made with large square blocks of local sandstone, sometimes bearing letters of the Greek alphabet, interpretable as quarry marks or as useful indications for their location in the building assemblies.

The city walls, built during the Lucanian occupation phase of the site, or in the mid-4th century BC, run about 2.5 km long, following the contour lines, on at least three sides of the mountain. It consists of two parallel curtains, interspersed with a filling of earth, stones and landfills. The external facing is made with large square blocks of local sandstone, sometimes bearing letters of the Greek alphabet, interpretable as quarry marks or as useful indications for their location in the building assemblies.

In this restored north-western section, a monumental door opened with the same construction technique as the walls. Initially it had an elongated rectangular compartment with double opening, with threshold and hinges, on which the three-wing wooden door was set. Subsequently, the room was narrowed into a corridor with the creation of two lateral compartments, with a reduction of the two-wing door.

The eastern monumental gate was discovered after the northwestern one. Both entrances to the city are characterized by the construction technique very similar to that of the fortification, as by the narrowing of the initial compartment and the wooden door from three to two doors, which occurred in the late fourth century BC, a few decades after the first construction . What distinguishes the two doors is the presence in the east of a dense paving pavement and likely steps due to the greater slope of this side of the mountain. At this door there is the reproduction of an epigraph in Greek language and characters which mentions a Lucan magistrate, nummelos, who would have commissioned the entire fortification work, probably at the moment when the Roman danger was beginning to be felt, the same that at the beginning of the following century it determined the violent end of the city.

The eastern monumental gate was discovered after the northwestern one. Both entrances to the city are characterized by the construction technique very similar to that of the fortification, as by the narrowing of the initial compartment and the wooden door from three to two doors, which occurred in the late fourth century BC, a few decades after the first construction . What distinguishes the two doors is the presence in the east of a dense paving pavement and likely steps due to the greater slope of this side of the mountain. At this door there is the reproduction of an epigraph in Greek language and characters which mentions a Lucan magistrate, nummelos, who would have commissioned the entire fortification work, probably at the moment when the Roman danger was beginning to be felt, the same that at the beginning of the following century it determined the violent end of the city.

Excavations carried out at the beginning of the 21st century have brought to light another section of the fortification in isodome blocks, about 50 m long, which in ancient times suffered the consequences of an important landslide phenomenon. An internal curtain ran parallel to it, built using an earlier wall (5th century BC). This fortification also constituted the perimeter wall of some contemporary houses. The presence of houses built in the vicinity of the contemporary fortification, perhaps for defensive purposes, is therefore also attested for the previous phase, of the fifth century BC. This is also what happened a century later, as evidenced by the discovery of a house at the north gate, which also seems to exploit blocks of the fortification of the mid-fourth century BC.

Excavations carried out at the beginning of the 21st century have brought to light another section of the fortification in isodome blocks, about 50 m long, which in ancient times suffered the consequences of an important landslide phenomenon. An internal curtain ran parallel to it, built using an earlier wall (5th century BC). This fortification also constituted the perimeter wall of some contemporary houses. The presence of houses built in the vicinity of the contemporary fortification, perhaps for defensive purposes, is therefore also attested for the previous phase, of the fifth century BC. This is also what happened a century later, as evidenced by the discovery of a house at the north gate, which also seems to exploit blocks of the fortification of the mid-fourth century BC.

The slope of the San Bernardo hill, called Braida, seems to have been occupied since the first quarter of the 6th century BC. Here in the sixties fragments of acroterial statues and painted relief clay slabs were found, which covered and decorated the roof beams, the slabs of the knights. This circumstance, combined with the discovery in the nineties of nine funerary objects, datable between the end of the sixth and fifth centuries BC, referable to the eminent group of the local community, that of the basileis (Greek word meaning: kings), made us think in the presence of a palatial complex, with functions not only residential, but also sacred and political.

The slope of the San Bernardo hill, called Braida, seems to have been occupied since the first quarter of the 6th century BC. Here in the sixties fragments of acroterial statues and painted relief clay slabs were found, which covered and decorated the roof beams, the slabs of the knights. This circumstance, combined with the discovery in the nineties of nine funerary objects, datable between the end of the sixth and fifth centuries BC, referable to the eminent group of the local community, that of the basileis (Greek word meaning: kings), made us think in the presence of a palatial complex, with functions not only residential, but also sacred and political.

On the slopes of Mount Giove, not far from the town, stands the ancient snow mill, one of the most important historical testimonies of the Municipality of Vaglio Basilicata. This artifact is made up of two circular bodies side by side: the first, the one with the largest diameter, is almost completely buried up to nine meters deep, the second smaller has structures in elevation similar to those of the ancient towers. The roofing structures have completely disappeared and the two structures are communicating with each other through an arched opening. The neviere are truncated-conical wells with rough stone perimeter walls, on average five or six meters deep and with a diameter of up to ten meters, which were used for a long time to store snow for consumption during the summer. We know from historical sources that between the mid-fourteenth century and the end of the nineteenth century, the use of natural refrigerant was widespread both for the preservation of perishable foods and as a cold therapy against certain pathologies. Once introduced into the pit, the snow, carried on the shoulder to the snow mill, was beaten and compacted layer by layer, then covered with dry foliage and a mobile conical canopy; between the roofing structure and the layer of leaves a thermal insulation cavity was created which allowed its conservation until the summer. It was above all the noble and upper middle class families who, during the seventeenth century, fueled a flourishing trade in natural refrigerant. The snow trade, in addition to satisfying the demands of the nobility, also had to satisfy the requests of merchants, hospitals, convents, etc., becoming so lucrative as to justify the application of a tax. Furthermore, it can be assumed that the second building of the Vaglio snow mill, that is the tower, could have function as a guardian to protect the ice itself.

On the slopes of Mount Giove, not far from the town, stands the ancient snow mill, one of the most important historical testimonies of the Municipality of Vaglio Basilicata. This artifact is made up of two circular bodies side by side: the first, the one with the largest diameter, is almost completely buried up to nine meters deep, the second smaller has structures in elevation similar to those of the ancient towers. The roofing structures have completely disappeared and the two structures are communicating with each other through an arched opening. The neviere are truncated-conical wells with rough stone perimeter walls, on average five or six meters deep and with a diameter of up to ten meters, which were used for a long time to store snow for consumption during the summer. We know from historical sources that between the mid-fourteenth century and the end of the nineteenth century, the use of natural refrigerant was widespread both for the preservation of perishable foods and as a cold therapy against certain pathologies. Once introduced into the pit, the snow, carried on the shoulder to the snow mill, was beaten and compacted layer by layer, then covered with dry foliage and a mobile conical canopy; between the roofing structure and the layer of leaves a thermal insulation cavity was created which allowed its conservation until the summer. It was above all the noble and upper middle class families who, during the seventeenth century, fueled a flourishing trade in natural refrigerant. The snow trade, in addition to satisfying the demands of the nobility, also had to satisfy the requests of merchants, hospitals, convents, etc., becoming so lucrative as to justify the application of a tax. Furthermore, it can be assumed that the second building of the Vaglio snow mill, that is the tower, could have function as a guardian to protect the ice itself.

The remains of a 290 m2 rectangular room are currently visible in the building, delimited by gray limestone blocks and partly paved by large flat white limestone bases.