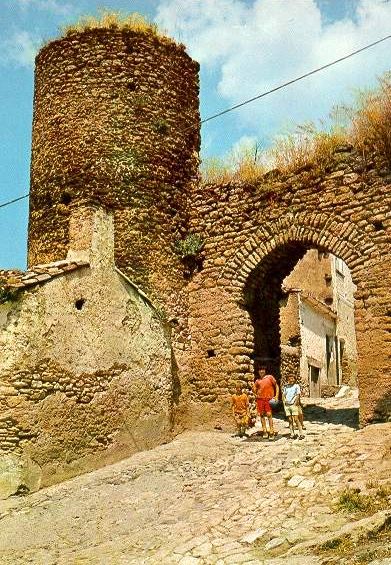

The arabic Tricarico overlooks the Basento river valley. Home of the mayor-poet Rocco Scotellaro, the city is known for "L’màsh-k-r", figures disguised as cows and bulls protagonists of the carnival. The medieval old town is among the most important and probably the best preserved in Basilicata, composed by the Arab districts Ràbata and Saracena and the Norman Monte Piano and the Civita, where roads and alleys take on different aspects depending on the dominating power by which they were set up. Among the numerous churches, one of the main Marian places in the region stands out: the Sanctuary of the Madonna di Fonti, reached out by many devotees on foot every year. The tall Norman Tower attached to the castle was probably built between the ninth and tenth centuries as a fortified fortress then modified during the Norman-Swabian period between XI and XIII. The landscape is surrounded by extensive woods populated by majestic and imposing oaks.

The arabic Tricarico overlooks the Basento river valley. Home of the mayor-poet Rocco Scotellaro, the city is known for "L’màsh-k-r", figures disguised as cows and bulls protagonists of the carnival. The medieval old town is among the most important and probably the best preserved in Basilicata, composed by the Arab districts Ràbata and Saracena and the Norman Monte Piano and the Civita, where roads and alleys take on different aspects depending on the dominating power by which they were set up. Among the numerous churches, one of the main Marian places in the region stands out: the Sanctuary of the Madonna di Fonti, reached out by many devotees on foot every year. The tall Norman Tower attached to the castle was probably built between the ninth and tenth centuries as a fortified fortress then modified during the Norman-Swabian period between XI and XIII. The landscape is surrounded by extensive woods populated by majestic and imposing oaks.

The history of Tricarico, deeply marked by the short Arab domination, seems to have started around 849, the period of the foundation of the Arab Emirate of Bari (847-871) and the year in which the first documented testimony about the city is first reported.

As much as other Lucanian towns such as Pietrapertosa and Tursi, the Arab-Berbers settled permanently, imprinting their traces in the urban fabric, as can be noticed by visiting the Ràbata and Saracena districts. A few decades later the Byzantines reconquered it, leaving their influence into Tricarico’s culture and traditions, up to the point that religious celebrations were performed according to Greek rite until the first half of the XIII century.

In 1048 it was taken by the Normans and by 1080 Robert Guiscard took possession of the feud. An important event, in the most recent events, Tricarico will have it with the figure of the poet and politician Rocco Scotellaro, who will be mayor very young (23 years old), from 1946 to 1948 and then until 1950.

The Norman domination and the role of Rocco Scotellaro have left indelible traces in the culture and architecture of Tricarico and its people.

The Norman domination and the role of Rocco Scotellaro have left indelible traces in the culture and architecture of Tricarico and its people.

Each symbol refers to the figure of Scotellaro, like the plaque affixed to his house: "Rocco Scotellaro: socialist mayor of Tricarico - poet of peasant freedom". While among the narrow and blind alleys of the historical center the verses of his poems resound, along a literary path built on wooden panels.

In the cemetery of Tricarico, just at the point where the meridionalist rests, his friend Carlo Levi ordered the construction of a real funerary monument, with a window over the hilly landscape, that “long slope of the Basento” always described by Scotellaro in the his works and on one of the stones the final verses of the poem Always new is dawn were engraved.

In the former convent of San Francesco, in Tricarico, most of the documentation belonging to the mayor-poet Rocco Scotellaro is kept.

In the former convent of San Francesco, in Tricarico, most of the documentation belonging to the mayor-poet Rocco Scotellaro is kept.

The center was founded in 2003 on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the death of the illustrious citizen of Tricarico and aims to preserve every testimony linked to him and the historical context, as well as managing a specialist library with works dedicated or written by Scotellaro on Meridionalism. The center also promotes research activities, conferences, exhibitions and publications in collaboration with Italian universities and cultural institutes, in order to stimulate the debate on Southern Italy.

Probably built between the 9th and 10th centuries as a fortified fortress, with a majestic 27 meters high tower, it was modified during the Norman-Swabian period, between the 11th and 13th centuries. It hosts a magnificent cycle of frescoes from the early seventeenth century made by the Lucanian painter Pietro Antonio Ferro. The tower has cylindrical shape and it is arranged on four floors and crowned with machicolations. It kept performing its military function until the XVII century, while the castle, in 1333, became the seat of a monastery of cloistered nuns, founded by at the time Countess of Tricarico, Sveva and suppressed in 1860. From 1930 the imposing manor houses the Convent of the Disciples of Jesus in the Eucharist.

Probably built between the 9th and 10th centuries as a fortified fortress, with a majestic 27 meters high tower, it was modified during the Norman-Swabian period, between the 11th and 13th centuries. It hosts a magnificent cycle of frescoes from the early seventeenth century made by the Lucanian painter Pietro Antonio Ferro. The tower has cylindrical shape and it is arranged on four floors and crowned with machicolations. It kept performing its military function until the XVII century, while the castle, in 1333, became the seat of a monastery of cloistered nuns, founded by at the time Countess of Tricarico, Sveva and suppressed in 1860. From 1930 the imposing manor houses the Convent of the Disciples of Jesus in the Eucharist.

In the center of Tricarico, it is one of the most significant buildings of historical, artistic and monumental interest. The palace preserves a sixteenth-century structure and it is developed in rooms with wooden ceilings and paintings of the XVIII c. Since March 2001 it is exposed a valuable collection of archaeological finds, reflecting the importance that the Basento valley got since the archaic age as a strategic road communication between the Jonian and Tyrrenic sides. From the atrium of the building, accessed through two stone portals, it is possible to enjoy a splendid and panoramic view of the Bradano and Basento valleys.

In the center of Tricarico, it is one of the most significant buildings of historical, artistic and monumental interest. The palace preserves a sixteenth-century structure and it is developed in rooms with wooden ceilings and paintings of the XVIII c. Since March 2001 it is exposed a valuable collection of archaeological finds, reflecting the importance that the Basento valley got since the archaic age as a strategic road communication between the Jonian and Tyrrenic sides. From the atrium of the building, accessed through two stone portals, it is possible to enjoy a splendid and panoramic view of the Bradano and Basento valleys.

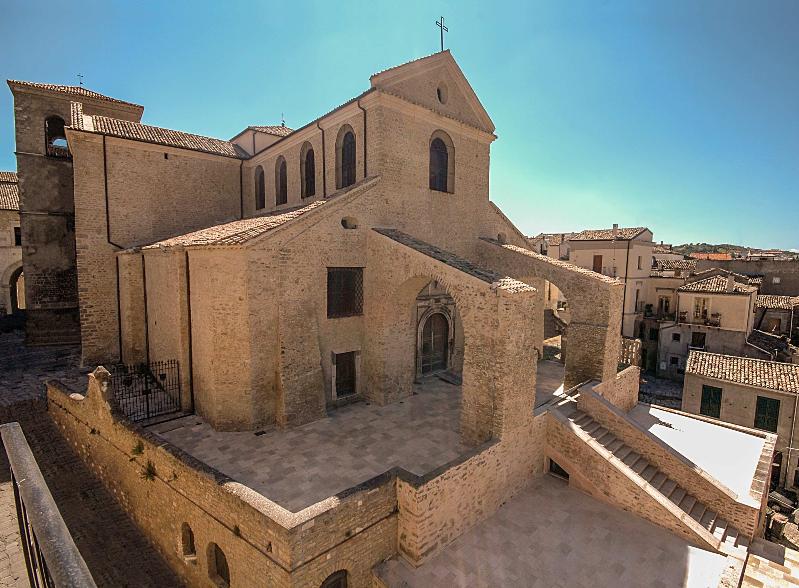

Its construction dates back to 1101, the Norman period, by will of Robert the Guiscard, count of Montescaglioso and lord of Tricarico. The previous Romanesque features, very similar to those of the cathedrals of Acerenza and Venosa, in the heart of Vulture, have been replaced by interventions in the Baroque style, on the initiative of local bishops. The cathedral of Tricarico, however, takes on its current appearance only between 1774 and 1777.

Its construction dates back to 1101, the Norman period, by will of Robert the Guiscard, count of Montescaglioso and lord of Tricarico. The previous Romanesque features, very similar to those of the cathedrals of Acerenza and Venosa, in the heart of Vulture, have been replaced by interventions in the Baroque style, on the initiative of local bishops. The cathedral of Tricarico, however, takes on its current appearance only between 1774 and 1777.

Inside, with a Romanesque layout, one can admire several paintings attributed to the Lucanian painter Pietro Antonio Ferro, as a Deposition and a Crucifixion. Also interesting, a triptych painted on the panel of the Madonna with Child between Saints Francis and Antonio, the panels of a polyptych depicting Saints Francis and Anthony, the Annunciation by Antonio Stabile and other valuable works dating back to the 16th century and attributed to the Lucanian Giovanni Todisco.

Of great beauty, the complex was built in 1333 in the pre-existing castle with the annexed chapel of the Crucifix frescoed by the seventeenth-century painter Pietro Antonio Ferro.

Of great beauty, the complex was built in 1333 in the pre-existing castle with the annexed chapel of the Crucifix frescoed by the seventeenth-century painter Pietro Antonio Ferro.

The church of the convent of Santa Chiara has a single large nave with a splendid coffered ceiling where a 16th century canvas depicting the Assumption is set. On the altars stand out a canvas that portrays the Porziuncola and another with the image of the Immaculate still attributed to the Lucanian artist Pietro Antonio Ferro.

On the central Piazza Garibaldi rises its beautiful bell tower with two bells which gives to it a truly elegant appearance. Founded in the 13th century and consisting of a single nave, the church of San Francesco is decorated with an ogival arched portal in the Apulian Romanesque style. In reality, the temple is attached to the convent of San Francesco founded in 1314 by Tommaso Sanseverino, count of Marsico and Tricarico, and by his wife Sveva, and it is one of the oldest Franciscan convents in Basilicata, whose structures were partly demolished or reworked. The church, instead, restored in 1882 and after the 1980 earthquake, dominates majestically over the town

On the central Piazza Garibaldi rises its beautiful bell tower with two bells which gives to it a truly elegant appearance. Founded in the 13th century and consisting of a single nave, the church of San Francesco is decorated with an ogival arched portal in the Apulian Romanesque style. In reality, the temple is attached to the convent of San Francesco founded in 1314 by Tommaso Sanseverino, count of Marsico and Tricarico, and by his wife Sveva, and it is one of the oldest Franciscan convents in Basilicata, whose structures were partly demolished or reworked. The church, instead, restored in 1882 and after the 1980 earthquake, dominates majestically over the town

It is located outside the historic center of Tricarico and it was built in 1605. The cloister has a great visual impact and it is embellished with paintings depicting biblical scenes that, in the lunettes, propose stories of the Carmelite order and, in the rounds, depict saints of the same order. The church has a single nave and is decorated with paintings by Pietro Antonio Ferro, with scenes from the life of the Madonna and Christ and episodes from the New Testament. Very beautiful is the painting of the Madonna del Carmine, placed on the main altar, and one with the Crucifixion and saints of 1616.

It is located outside the historic center of Tricarico and it was built in 1605. The cloister has a great visual impact and it is embellished with paintings depicting biblical scenes that, in the lunettes, propose stories of the Carmelite order and, in the rounds, depict saints of the same order. The church has a single nave and is decorated with paintings by Pietro Antonio Ferro, with scenes from the life of the Madonna and Christ and episodes from the New Testament. Very beautiful is the painting of the Madonna del Carmine, placed on the main altar, and one with the Crucifixion and saints of 1616.

There are several archaeological areas: Serra del Cedro (Lucanian city of the sixth century BC), Piano della Civita (Lucanian city of the fourth century BC), Calle (Roman settlement, with thermal plant), Sant'Agata (Roman villa with polychrome mosaic floor).

The site is very extensive. The walls, entirely identified, contain an area of about 60 hectares within which many foundations of houses have been found and has been identified and partly explored an artisan area.

The site is very extensive. The walls, entirely identified, contain an area of about 60 hectares within which many foundations of houses have been found and has been identified and partly explored an artisan area.

The human presence on the site of Serra del Cedro dates from the middle of the 6th century B.C. and continues for the 5th and 4th centuries B.C. In the second half of the 4th century B.C., the city experienced a phase of expansion that lasted a few decades. Every archeological record, in fact, it is interrupted at the beginning of the third century B.C. Its destruction is probably connected to the war events that took place on the territory of Lucania and that ended in the first decades of the second century B.C. when Rome completed the conquest of Magna Grecia after having destroyed Taranto, in 272 BC.

The settlement, located in the homonymous district, is at the center of a dense road system. Its exploration is only at the beginning and, to date, has been able to ascertain a phase of expansion between the second and the first century BC, an era which dates back to an important thermal plant with mosaic floor (the mosaic is now exhibited in the National Archaeological Museum Domenico Ridola Matera).

The settlement, located in the homonymous district, is at the center of a dense road system. Its exploration is only at the beginning and, to date, has been able to ascertain a phase of expansion between the second and the first century BC, an era which dates back to an important thermal plant with mosaic floor (the mosaic is now exhibited in the National Archaeological Museum Domenico Ridola Matera).

The city of Calle was a center of ceramic production until the fifth, sixth century A.D. with products spread in a vast territory that exceeds the borders of the current region.

In Tricarico, in the "Piano della Civita" area, an extended plateau high m. 930 above sea level and overlooking the middle valley of the Basento river, there is a fortified settlement known since the last century for its walls and a small temple whose structures rose at least a couple of meters above the countryside. In the thirties the wall structures emerging on the ground were subjected to a systematic stripping for the construction works of the nearby motorway subsequently what still remained of the ancient buildings was covered by an accumulation of stones piled up by the peasants to free the cultivable areas from the stone materials that were found frequently and which made plowing difficult.

Since the establishment of the Archaeological Superintendency of Basilicata, the location has always been the subject of the topographical investigation, thanks to the help of aerial photos, a system of three walls has been identified, the outermost of which, following the steep edges of the rocky bank elevated over the surrounding countryside, it encompasses all the vast plateau whose elevation profile slopes gently from East to West towards the Basento.

The city of Piano della Civita, whose most ancient moment seems so far datable to the glimpse of the fourth century B.C. or in the first decades of the third century B.C., it is located in the center of an area where, in the same period in which it was born and is inhabited, large fortified inhabited centers and sanctuaries experienced a phase of expansion and then experienced a slow and progressive abandonment which was completed during the III sec. B.C. This is the case of the nearby fortified cities of Croccia Cognato, Serra del Cedro, Serra di Vaglio and the large sanctuary of Garaguso.

In the territory of Tricarico numerous villas have been identified which, in most cases, have a continuity of life which starting from the 4th century B.C. in conjunction with the expansion phase of the fortified centers it goes up to the IV-V century A.D., overcoming the chronological thickness of the public buildings of Piano della Civita whose existence ends in the first century A.D. These settlements, while bearing witness to their persistent vitality of the socio-economic formula based on the family-run farm, the owner's place of residence and the processing of agricultural products, at the same time show a type of population which is numerically intense and economically prosperous but organized in autonomous production micro-structures.

The settlement of Civita had a political-administrative function in the surrounding area and the close relationship with the Santuary of Rossano has in some way enhanced this function: the topographical proximity, the connection ensured by a comfortable road that can still be traveled, the presence of the materials Rossano epigraphs of tiles bearing the Oscan CE KAd stamps found in large quantities in Tricarico among the collapses that mark the abandonment of the area and epigraphs showing dedications that mention magistrates and political structures coeval with the buildings of Civita, are elements that bring the settlement of Tricarico stands out in a singular way. Its political-administrative function constitutes an important novelty if one considers that at the end of the third century B.C. Lucania was devastated and repeatedly plundered by the continuous wars that took place on its territory almost without interruption starting from 297-295 until 206 B.C. expresses a picture in which the only urban realities are the colonies of Grumentum, Venusia, Heraclea federated city and perhaps also Metaponto.

Speech held at the meeting "The Arabs in Basilicata. A conference in Tricarico"

Tricarico, Ducal Palace, Saturday, December 3, 2011, at 10.00

Carmela Biscaglia

The geographical configuration of Basilicata, as a land inserted in the Mediterranean ecumene, has always prepared this area of Italy for the meeting of different cultures, coexistence between ethnicities, interchange with the Middle East and North African civilizations. Many components of its medieval and modern history have, therefore, been conditioned by it in more or less persistent ways and forms, the traces of which have come down to us. This is the case of the Arab-Muslim presences, whose permanences are an integral part of the heritage of the history and culture of Basilicata and Tricarico in particular

The Arabs already in the IX and X centuries had touched with violent incursions vast areas of southern Italy and transformed Bari into the seat of one of their emirates (847-871). Their armies included Islamized people of Camitic origin from North Africa, better known as Berbers or Saracens, involved in the process of Arab Muslim acculturation and in the expansion of Islam towards the West as a function of Maghreb contingents. The Saracens pushed into the inner areas of the South and reached Basilicata, taking advantage of the valleys to carry out robberies and make prisoners to be used as slaves in the centers of the Islamic Mediterranean Empire at the time of its greatest expansion. In 872 sacked Grumento, in 907 occupied Abriola and Pietrapertosa, in 994, according to Lupo Protospata, occupied Matera after having besieged it for three months Over the initial political-religious conflict, due to the aggressive violence of their imposition, these populations soon had to set up quarters in the highest or most strategic centres of Basilicata and gradually manifest their soul as merchants, artisans and farmers experts in the cultivation of arid areas, intertwining with indigenous peoples intense relations of peaceful coexistence as well as economic and cultural exchange.

The geographical configuration of Basilicata, as a land inserted in the Mediterranean ecumene, has always prepared this area of Italy for the meeting of different cultures, coexistence between ethnicities, interchange with the Middle East and North African civilizations. Many components of its medieval and modern history have, therefore, been conditioned by it in more or less persistent ways and forms, the traces of which have come down to us. This is the case of the Arab-Muslim presences, whose permanences are an integral part of the heritage of the history and culture of Basilicata and Tricarico in particular

The Arabs already in the IX and X centuries had touched with violent incursions vast areas of southern Italy and transformed Bari into the seat of one of their emirates (847-871). Their armies included Islamized people of Camitic origin from North Africa, better known as Berbers or Saracens, involved in the process of Arab Muslim acculturation and in the expansion of Islam towards the West as a function of Maghreb contingents. The Saracens pushed into the inner areas of the South and reached Basilicata, taking advantage of the valleys to carry out robberies and make prisoners to be used as slaves in the centers of the Islamic Mediterranean Empire at the time of its greatest expansion. In 872 sacked Grumento, in 907 occupied Abriola and Pietrapertosa, in 994, according to Lupo Protospata, occupied Matera after having besieged it for three months Over the initial political-religious conflict, due to the aggressive violence of their imposition, these populations soon had to set up quarters in the highest or most strategic centres of Basilicata and gradually manifest their soul as merchants, artisans and farmers experts in the cultivation of arid areas, intertwining with indigenous peoples intense relations of peaceful coexistence as well as economic and cultural exchange.

These installations were consistent and of long duration in many centers of the middle basin of Bradano and Basento, of the lower Potentino from Pietrapertosa to Abriola and of the Agri Valley. The widespread, but still little explored architectural traces of Arabomusulman imprint that can be found there, show that they were not only groups of soldiers, but real communities that, exploiting their political and military dominance, drew local advantages, to increase and expand their trade, the true soul of Arab culture.

These installations were consistent and of long duration in many centers of the middle basin of Bradano and Basento, of the lower Potentino from Pietrapertosa to Abriola and of the Agri Valley. The widespread, but still little explored architectural traces of Arabomusulman imprint that can be found there, show that they were not only groups of soldiers, but real communities that, exploiting their political and military dominance, drew local advantages, to increase and expand their trade, the true soul of Arab culture.

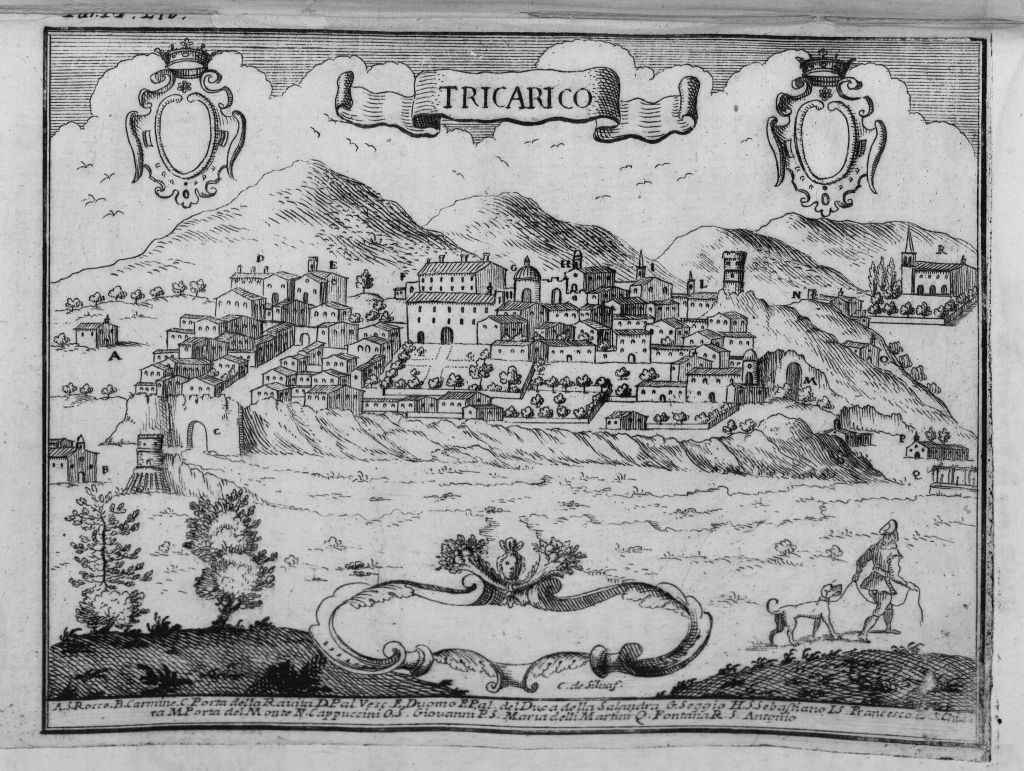

From the initial military border garrisons for the concentration of militias engaged in war (ribàt), in fact, then grew real Islamic residential districts (Rabatane), still strongly visible in the urban fabric of Tursi, Tricarico and Pietrapertosa, centres where their settlements had to be more durable in neighborhoods that, recalling the fascinating North African ribàt, the local tradition connòta still today as Rabate or Rabatane. All highlight the function of control of the valleys below: the Rabatana of Tursi, in an overprotected position with its construction complex dominated by the imposing castle, controlled the village of Anglona and the valleys of Sinni and Agri; the Rabata and the Saracena of Tricarico the valleys of Bradano and Basento, valley - the latter - which dominated with its castle largely dug into the rock, from above its more than 1,000 meters of altitude, also the Arabata of Pietrapertosa.

Further traces of the Arabic presence in Basilicata are to be found in the dialects, where the Arabic loans essentially concern the terminology and commercial expressions, but there are also linguistic contributions Arab-Berber with repercussions in the sphere of anthroponyms and toponyms, nicknames, epithets, food, housing, land ownership, fruit and vegetable products, many household items and clothing. Suffice it to recall, for example, terms such as musàl (tablecloth), ra'anàte (meat, fish, potatoes or other food scented with oregano and various spices and cooked on the grill), ciuféca (disgusting drink), celèpp (sugar densely dissolved in water to cover confectionery), surbètt (snow treated with cooked must), scerrà (bickering), tavùt (coffin), za'aglia (tape) and zuquarèdd (rope), zzirr (copper or terracotta container to contain liquids, especially oil).

The most valuable archive document for the rarity and the material that transmits us on the relations between indigenous peoples of Lucania and Arab-Muslim peoples in the 11th century, is the Greek parchment of Tricarico which, among other things, says: «Luokas the unbeliever and the apostate had also occupied the Kastellion of Pietrapertosa and, not content to multiply in all Italy (Byzantine) oppressions and robberies, had taken possession of other people’s lands as a brigand: so he took the territory of the kastron of Tricarico, of which the inhabitants had been owners for a long time and no longer allowed them to enter their lands to cultivate them. We then expelled from Pietrapertosa Loukas and his co-religionists and then the inhabitants of the kastron of Tricarico filed a complaint concerning the limits of their territory. We therefore summoned the taxiarch Constantine Kontou who brought with him the inhabitants of the kastellion of Tolve: with the agreement of the two parties, he restored the limits of the lands of Tricarico and Acerenza which were formerly [...]»

The most valuable archive document for the rarity and the material that transmits us on the relations between indigenous peoples of Lucania and Arab-Muslim peoples in the 11th century, is the Greek parchment of Tricarico which, among other things, says: «Luokas the unbeliever and the apostate had also occupied the Kastellion of Pietrapertosa and, not content to multiply in all Italy (Byzantine) oppressions and robberies, had taken possession of other people’s lands as a brigand: so he took the territory of the kastron of Tricarico, of which the inhabitants had been owners for a long time and no longer allowed them to enter their lands to cultivate them. We then expelled from Pietrapertosa Loukas and his co-religionists and then the inhabitants of the kastron of Tricarico filed a complaint concerning the limits of their territory. We therefore summoned the taxiarch Constantine Kontou who brought with him the inhabitants of the kastellion of Tolve: with the agreement of the two parties, he restored the limits of the lands of Tricarico and Acerenza which were formerly [...]»

This document, coming from the Chapter Archive of Tricarico and made known by two great scholars of Byzantine history, André Guillou and Walter Holtzmann, is an act written by the catepano Gregory Tarchanéiôtes in December 1001, and is a rare testimony of the Saracen presence in Tricarico (and generally in Basilicata). The document, of exceptional importance for the history of the Byzantine institutions in Southern Italy, attests to continued aggression by Muslim gangs, led by a Christian convert to Islam, the kafir Loukas, had founded in the fortified village of the ancient Pietra Perciata (Pietrapertosa), among the most inaccessible mountains of the Lucanian Apennines, a brutal tyranny and there sown terror. That the occupation of the most fertile territories of the fortified city of Tricarico had been of long duration, is testified by the subsequent intervention of the Byzantine chartoularios (cartographer) Myrôn, who had the task of redefining the boundaries of the countryside of Tricarico compared to that of Acerenza (which also included Tolve).

This document, coming from the Chapter Archive of Tricarico and made known by two great scholars of Byzantine history, André Guillou and Walter Holtzmann, is an act written by the catepano Gregory Tarchanéiôtes in December 1001, and is a rare testimony of the Saracen presence in Tricarico (and generally in Basilicata). The document, of exceptional importance for the history of the Byzantine institutions in Southern Italy, attests to continued aggression by Muslim gangs, led by a Christian convert to Islam, the kafir Loukas, had founded in the fortified village of the ancient Pietra Perciata (Pietrapertosa), among the most inaccessible mountains of the Lucanian Apennines, a brutal tyranny and there sown terror. That the occupation of the most fertile territories of the fortified city of Tricarico had been of long duration, is testified by the subsequent intervention of the Byzantine chartoularios (cartographer) Myrôn, who had the task of redefining the boundaries of the countryside of Tricarico compared to that of Acerenza (which also included Tolve).

At the dawn of the year 1000, Tricarico was, therefore, a Greek citadel, equipped with solid fortifications to defend its particular military configuration and its geographical position along the dividing line, hard contended by the Byzantines and Lombards throughout the tenth century, that is, the western border of the theme of Longobardia. Already included in 849 in the Lombard gastaldate of Salerno, it had then passed under Greek rule and became the seat of an Orthodox diocese in 968, when the Byzantine government established the theme of Lucania (968-969 ca) with Tursicon (Tursi) and completed the plan of hellenization of the Catepanate Church, creating new bishops in Gravina, Acerenza, Matera, Tursi, Tricarico, all suffragans of Otranto. Tricarico, at that time, was strongly imbued with spirituality as evidenced by the presence of the Italian-Greek monastic community of Santa Maria del Rifugio, which in 998 had given birth to a korion (economic-religious community)in the homonymous valley close to the left side of Basento. Here the igumen Kosmas, with the participation of foreigners and eléuteroi, that is, of peasants free from obligations towards the tax, had made the area part of that great movement, that characterized the whole Europe, of tillage of land with the cutting and burning of the thickets, and relative economic prosperity, as well as population growth

Despite the "great fear", which for almost 200 years (9th and 11th centuries) the endemic Saracen raids generated and the climate of hostility of the Byzantine government towards the Saracen Islamized populations, It is possible, however, a more realistic and lasting insertion of these in the social and economic fabric of many Lucanian centers starting from Tricarico.

The Saracens were certainly attracted by the rebirth that characterized the city as all the centers of the valley of Basento, in the first decades of the year 1000, where the increase in the demand for consumer goods, which had stimulated agriculture, was the cause and consequence of population growth, also favoured by Greek immigration and, probably, by Arab presences. These have, moreover, had to be transformed into other elements of development, in particular in the agricultural and commercial sector, revitalising arboriculture and horticulture, with the spread of Arab irrigation techniques, similar to those made in the areas on the edge of the Sahara, so well studied by Pietro Laureano, which, as we all know, is a tricaricesi. It was precisely this positive context that would provoke the subsequent invasions of the Normans, who would occupy Tricarico in 1048 in a battle fought under its walls, taking it from the Byzantines.

The Saracens were certainly attracted by the rebirth that characterized the city as all the centers of the valley of Basento, in the first decades of the year 1000, where the increase in the demand for consumer goods, which had stimulated agriculture, was the cause and consequence of population growth, also favoured by Greek immigration and, probably, by Arab presences. These have, moreover, had to be transformed into other elements of development, in particular in the agricultural and commercial sector, revitalising arboriculture and horticulture, with the spread of Arab irrigation techniques, similar to those made in the areas on the edge of the Sahara, so well studied by Pietro Laureano, which, as we all know, is a tricaricesi. It was precisely this positive context that would provoke the subsequent invasions of the Normans, who would occupy Tricarico in 1048 in a battle fought under its walls, taking it from the Byzantines.

The consequences of the long stay of the Saracens in Tricarico are attested not only by the persistence of the toponyms Rabata and Saracena and other Arabic-Berber language survivals found in the local dialect, as well as the urban context for the presence of the neighborhoods of Rabata and Saracena, which during the Middle Ages was also a counterbalance to a Giudecca and, in the sixteenth century, a large Albanian community.

It is likely that in that interweaving of civilizations coexisted in Tricarico, were the Jews, present in the city until the early 1500s with an industrious Jewry and its synagogue, to mediate the Arab culture in the town where, on the commission of the Jew David Menachem Zarfati of Tricarico, came the Hebrew version of the Perfect Jewel, medical work of the Arab Abul Qasim al-Zahrawi, the major representative and the great master of Hispanic-Arabian surgery of the early years of the thousand, copied to Melfi between 1452 and 1454 and now kept in the National Library of Paris.

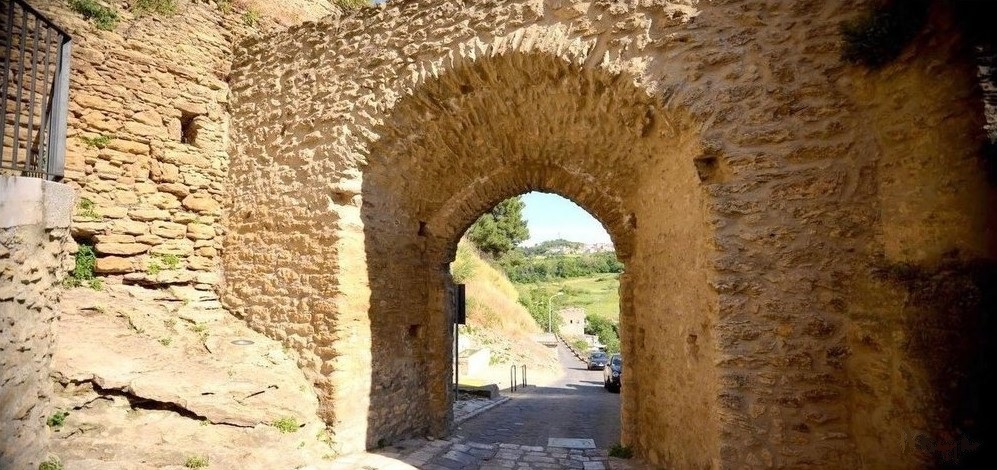

The wonderful, precious and rare view depicting Tricarico, printed in 1618 in Cologne by George Braun and Franz Hogemberg, effectively outlines the two districts of Rabata and Saracena that, with their walls, the terraced gardens, the hemiphoric towers to protect the relative doors of access, between which the Rabatana door that still insists with its original Islamic acute arch, testify the long episode of settlement of the Arabs in this town.

The wonderful, precious and rare view depicting Tricarico, printed in 1618 in Cologne by George Braun and Franz Hogemberg, effectively outlines the two districts of Rabata and Saracena that, with their walls, the terraced gardens, the hemiphoric towers to protect the relative doors of access, between which the Rabatana door that still insists with its original Islamic acute arch, testify the long episode of settlement of the Arabs in this town.

The urban events of these and other ribàt of Basilicata, such as that of Tursi or Pietrapertosa that, from fortified border installations responsible for the concentration of militias used in war attacks, then became Rabatane, or Arab residential neighborhoods.

The same applies to the etymology of the term Rabata: from Arabic ribãt (whose Maghrebi pronunciation gives name to the city of Rabat) with reference to "place of horses, place of rest; shelter for travellers, caravanserai; fortified border post, fortress of warrior monks", or to rábbatu "inhabited nucleus placed on high ground", as we read in the Glossary of urban terms of the Islamic world, edited by Paolo Cuneo and Ugo Marazzi.

The Saracena and the Rabata of Tricarico, however, still keeping distinct the two urban types, symbolically represent the evolutionary phases: of the one is, in fact, distinguishable the character of fort or first quartering on the extreme North offshoot of the rock spur on which rises Tricarico, to look out for the valleys of Bradano and Basento; of the other - the Rabata - are evident features of a core of expansion in S-E of the town, which bears very clear signs of the Islamic settlement tradition: the town of Rabata, in its compact structure is divided into two areas by a very narrow main road, the Arab shari, one to the east behind the walls and the other to the more developed west; from it depart the secondary streets or Darb, which intertwine in various directions and often end in dead ends or sucac, that define small residential tissues well distinguished from each other.

The housing units, often hypogeal, with modest building technique, not deprived of architectural dignity, if they tend to close in defense of the outside, with this, however, communicate through the facing terraces on arid land planted with orchards, They are the crown of the present-day medieval town of Tricarico and degrade on the lower slopes of the Milo stream, whose bed is divided into a myriad of gardens, irrigated by techniques of channeling spring water Arab plant.

These are crops that since the ninth-twelfth century, that is from the Byzantine-Arab-Norman period, have continued over the centuries, as documented by the a code of Tricarico of the late sixteenth century, which handed down the existence of a large number of "horti seu frutteti" (ochards) located outside the walls and the gates of Tricarico, but that were found in all the medieval cities of southern Italy and were intended for small production for the sale and consumption within the city community. The code distinguishes horti from orchards, the latter term also used with its synonym of "garden".

These are crops that since the ninth-twelfth century, that is from the Byzantine-Arab-Norman period, have continued over the centuries, as documented by the a code of Tricarico of the late sixteenth century, which handed down the existence of a large number of "horti seu frutteti" (ochards) located outside the walls and the gates of Tricarico, but that were found in all the medieval cities of southern Italy and were intended for small production for the sale and consumption within the city community. The code distinguishes horti from orchards, the latter term also used with its synonym of "garden".

Let us think, for example, of the "garden" of the bishop’s menseroom, commonly called "bishop’s garden", existing in the area between the monastery of Carmine, the chapel of St. Rocco (now non-existent) and placed above the caves of Ravita. It was an orchard located along the slopes of the Rabata, corresponding to the right side of the Vallone delli Lavandari and overlooking the area called Porta della Ravata. The products of these orchards for the costs of management that involved, - it is worth mentioning - nevertheless constituted a privileged food of the noble and ecclesiastical class.

The horti, instead, dominated the lower part of the Vallone delli Lavandari today called the Caccarone valley, basin of S. Antonio and Milo stream, an area rich in spring water and used for the cultivation of vegetables, sold on the local market. It was also the area of public fountains and public wash house, where the use of water was not taxed.

The set of these gardens and orchards represented a sort of appendage, completing the palaces of the nobility between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Even the bishop had some, as well as the University (Municipality), which used these more or less extensive areas of the state for the small pasture, or to hold fairs and periodic markets. These gardens and gardens, small fertile patches of land, delimited by dry stone walls, formed the first ring of the suburban cultivations with Mediterranean tree species, which benefited and benefit from the presence of the abundant channeled spring water, is of a more protected and mild microclimate favoured by the river bed itself.

It is not uncommon to find in the lease contracts of similar gardens or orchards still of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the explicit reference to the works of canalization and construction of water collection tanks, generally borne by the owners of the funds and the payment of annual fees for finding water sometimes provided by neighbors. There were also disputes.

Just to understand the value of similar crops within that use of the territory and its resources that more wisely characterized the past, we recall that at this first ring of gardens and gardens, which surrounded the city, followed in a concentric manner that of the vineyards, then vineyards and olive groves, then the large cereal extensions and, finally, at the closure of the municipal farm, the vast wooded areas of state property nature.

Just to understand the value of similar crops within that use of the territory and its resources that more wisely characterized the past, we recall that at this first ring of gardens and gardens, which surrounded the city, followed in a concentric manner that of the vineyards, then vineyards and olive groves, then the large cereal extensions and, finally, at the closure of the municipal farm, the vast wooded areas of state property nature.

In the cultivation of these suburban lands, which first Pietro Laureano defined "Saracen gardens" for the connections found and detectable in the Saharan areas and other archaic sites of southern Italy and Cappadocia, the Arabs had to prove their hydraulic ability. Exploiting the waters of the numerous springs drained by the rocks on which Tricarico rises and channeling the rains, before they converged and dispersed in the underlying "uaddone", they organized a system of capillary irrigation, used for centuries - as I have just illustrated - and whose signs can still be seen today. And it is equally probable that also in Tricarico the Arabs had introduced those varieties of tree species typical of the Mediterranean gardens, often mentioned in the documents: the cedars, the lemons, the bitter oranges called "cetrangoli" the only citrus fruits of this type known in the Mezzogiorno until the end of the fifteenth century, when the sweet oranges spread. The springs also attest to the willows and mulberries.

These are products that fed a lively economy, all regulated by the municipal statutes, which entered into the merit of the theft of fruit, salads and willows, as well as damage in various respects to the "hanging fruits" in the gardens and sprouts in the vegetable gardens, both by men and by grazing animals. A matter, of course, then as today, joy and delight of the market gardeners, subjected to municipal taxes, called "gabelle".

Conclusion: the Rabata and the Saracena of Tricarico are unique in the South as a testimony to urban and landscape remained almost unchanged for centuries. It is therefore the responsibility of all of us to safeguard and protect this historical and cultural heritage and identity of great value, which underlies a wise use of the interrelations between city and nature, and that should be protected first of all by appropriate legislative measures relating to the area of gardens and gardens. A "park of gardens and suburban gardens".

Conclusion: the Rabata and the Saracena of Tricarico are unique in the South as a testimony to urban and landscape remained almost unchanged for centuries. It is therefore the responsibility of all of us to safeguard and protect this historical and cultural heritage and identity of great value, which underlies a wise use of the interrelations between city and nature, and that should be protected first of all by appropriate legislative measures relating to the area of gardens and gardens. A "park of gardens and suburban gardens".

Safeguard and protection that will be guaranteed and, in my opinion, well accepted by the population itself, if they come back to relive in the perspective for which these neighborhoods and these vegetable gardens were originally designed and lived: a view of maintaining human presence and maintaining an economy, but also of respecting the reasons of the territory (think of the importance of water regimentation). It is, in fact, a matter of protecting and enhancing a good that is in its overall urban and landscape, a good that today is defined of the urban landscape, precisely because of the evident interrelation between inhabited and nature, between the needs of the city and the use of its territory. Enhancing a good not only and not so much for purely aesthetic purposes, but restoring its original potential as an economic resource.

It is in this organic dimension that the "urban gardens" have always been a fundamental part of European architectural and economic culture, and towards which today address the cultural models of the sustainability of urban areas and the role of public greenery within cities.