The Lucanian Dolomites are the mountainous relief that in the heart of Basilicata characterizes the landscape with spectacular pinnacles and shapes that have suggested fanciful names such as the golden eagle, the anvil, the great mother, the owl. Located to the east of the most impressive Pierfaone-Volturino-Viggiano ridge of the Lucanian Apennines, the Small Lucan Dolomites constitute the heart of the homonymous regional natural park (which extends to the forests of Gallipoli-Cognato). They are called Dolomites due to the morphological similarity with the most famous Venetian mountains. The birth of the mountain group, which dominates the central part of the Basento valley, dates back to 15 million years ago. The steep peaks shaped by the millennial action of atmospheric agents, have sharp spiers with an average altitude of around 1,000 meters s.l.m. The highest peaks are those of M. Caperino (1455 m) and of M. Impiso (1319 m).

The territory presents an alternation of oak woods and barren and rocky peaks on which, however, a rare and interesting flora thrives with peculiar plant species such as the red valerian, the annual lunaria and the onosma lucana. The fauna, in addition to wild boar (numerous), presents a remarkable variety of birds: red kite, swift, kestrel, royal crow and peregrine falcon. Moreover due to the distance from the seas, the climate is characteristic of the mid Apennine mountains: harsh winters, with a prolonged presence of snow on the ground (up to two, three months), and cool, windy summers. Rainfall is around 1,000 mm per year.

Pietrapertosa was founded by the Saracens in the second half of the 9th century, at a time when, in addition to having created an ephemeral emirate in Bari (847-871), they occupied Tursi (850) and Tricarico, and after more than a millennium today deep and indelible traces are still encountered like the Saracen castle and the area of Arabata, the first nucleus of this delightful town. After the fall of Bari (871), the Byzantines launched a large-scale offensive to reconquer Puglia and Basilicata from the Saracens and the Lombards. Subtracting the western part of historical Lucania from the Lombard Principality of Salerno, the future Basilicata will be organized as the Thema of Lucania with the capital Tursi. Towards the end of the 10th century, following a resumption of the Muslim offensive, a group of Saracens headed by a Greek who converted to Islam, Loukas, reoccupied Pietrapertosa and the surrounding countryside. The inhabitants of the nearby Tricarico asked for the intervention of the Catapano.

Like other sites chosen by the Arabs to settle down, also this one in Pietrapertosa presents itself to the landscape with a double attitude: one concealed and facing outwards with a defensive outlook and the other, more secure and open inward but still defensive in the maze of the rabatana. Here the alleys, lockable at the entrance, ended in a blind bottom, sometimes close to the cliff, where streams of land make their way for minuscule orchards, cleverly interconnected with steep and partially excavated imbibition channels.

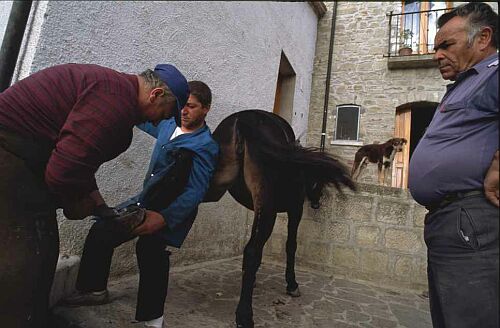

The theme of the fortress, the cliff and the castle that merges into it, often stands out as the dominant theme of many villages and towns, but here there is more. There is an imposing theme that extends to the whole settlement and that is articulated at the various scales from large to domestic, in which it is not uncommon to discover direct connections with the cliff of the single houses or of the open spaces in the rocky interlacing. At the bottom of these, in the corners, a twisted fig may appear as soon as possible, where the donkey who lives together, is the most suitable way to move through the narrow and impervious corridors between the houses.

There is also a real phenomenon of monumental inversion that is not recognizable in a particular building emerging between the houses as it could be a castle or a cathedral. Here, on the fabric, there is a series of boulders from the Lucanian Dolomites that popular imagination has connoted with names of recognition. Hiding among these monumental natural architectures, in the impregnable center of the region, the Arabs have been able to castle, longer than elsewhere, to look at without being seen.

The most ancient attestations concerning the presence of fortified structures in Pietrapertosa date back to the beginning of the first decade of the XI century and come from a document where in 1001 or 1002 the protospatario (byzantine official) Gregorio Tarchaneiotes, Catapano of Italy, redetermines the boundaries between Acerenza and Tricarico after having driven out a group of armed Saracens from Pietrapertosa.

Archaeological excavations made possible the identification of three different phases of expansion of the castle, towards the access gate, as evidenced by the presence of several facades remains. At the time of maximum expansion part of the entrance was made up of three floors closed by a system of drains used as the defense at the entrance.

Some buildings consisted of a basement and an above-ground floor, later collapsed over the walls facing the town. Down below the walls, a large terrace with incompleted archaeological excavations, used to be a space servicing the castle but with not yet investigated functions and a probable second access to the town. In this area there is an early medieval necropolis, formed by arcosolium burials with niches and deposition space dug directly into the rock of some sandstone spiers, anciently reachable with removable stairs.

Another spire, on the other hand, houses a lookout point, isolated from the fortified walls and dug into the rock. Finally, a staircase, still existing, directly carved into the rock, led to the top of the rocky peak where the castle stands, which allowed the "at sight" control over a large territory. In the castle there are two cisterns for collecting rainwater. In the deepest, the remains of a medieval wooden log were preserved, buried in the slime. Adjacent to the entrance portal, the original stairway leading to the upper square came to light and a series of walls leaning against each other, testifying to three phases of expansion of the walls. To the medieval phase of the castle belong a semi-rocky room, used for healing, a large underground space divided into two rooms by a stone arch, mostly preserved in place and a small room carved into the rock that documents the presence of a stabling for animals. The fortified wall preserves evidence of medieval construction technique characterized by the use of "diatones" in wood or small wooden beams stuck crosswise in the walls according to a precise geometric mesh, to improve the efficiency of the walls.

Castelmezzano was recently elected as one of the most beautiful towns in Italy and rises 750 meters above sea level in the Regional Park of Gallipoli Cognato and the Lucanian Dolomites as well as Pietrapertosa, the other small village of the Dolomites of Basilicata located at 1088 meters above sea level. sea. The complex of rocks and sandstone spiers carved by water and wind that have given rise to a fairytale landscape. Like Pietrapertosa, Castelmezzano also has a long history that dates back to the early Middle Ages but due to its different origins there has always been a strong rivalry between them.

According to an ancient tradition Castelmezzano was founded in the 10th century by fleeing people. To escape were the inhabitants of a village in the Basento valley threatened by the arrival of the Saracens. During their exodus they recognized in these rocks and gorges of the Lucanian Dolomites an ideal shelter: from here one could bombard the possible enemy with a rain of stones. It is not clear if later the new center of Castelmezzano was occupied by the Saracens and reconquered by the Byzantines in the military campaign launched in the aftermath of the expulsion of the Saracens from Bari, but the castle that was built which only a few ruins remain is from the Norman period. The position of “castle in the middle” (castel di mezzo) between Pietrapertosa and Brindisi di Montagna, is at the origin of the name.

To watch it in the distance, Castelmezzano, so small and graceful, brings to life the feeling of entering a fairy tale, whose protagonists are the golden eagle and the Owl, the Great Mother, the Anvil and the Mouth of the Lion. Only the names are borrowed from the imagination, because the sculptures of the huge boulders of sandstone rock, which over time have been shaped by the games of wind and rain, to take on similar shapes, really exist! Guarding this medieval jewel, made of steep stairs, narrow alleys, houses climbing on the rock, are the Lucanian Dolomites that, higher up, following dedicated paths, reveal an more enchanting landscape.

The place is already fantastic in itself, with this landscape of rock, with the dark gray-sandstone that seems to swallow it, wrapping it in a cone of shadow when evening falls, and the mysterious walkways of the Norman sentinels. Then there is the magic, because here the ""magyars"" existed and everyone somehow believed in the evil eye, the "munaciedd" that frightened children and the pummunar, the werewolf. The inhabitants retain the characteristics of the peasant culture: suspicious, tenacious, loyal and hospitable, they are the children of a mean land that has hardened them due to the harshness and difficulties of life. After centuries of miserable cultivated fields, of men who cut fagots and twigs of thorns, of herds that wander to contend to the rock some leaves, of landslides due to senseless deforestation, today they discover their reward: healthy air, temperate and dry climate , mountains covered with thick woods and verdant meadows

The two centers, Castelmezzano and Pietrapertosa are connected by the ‘Sentiero delle Sette Pietre’, one and a half hour naturalistic trek. A journey into fantasy and tradition but also the "Flight of the Angel" is very spectacular and takes place in the summer period (between June and September). Tied by a special harness and attached to a sturdy steel cable, this journey starts suspended in the air from Castelmezzano to arrive at Pietrapertosa (or vice versa) at a speed of about 120 km / h and the same procedure is repeated to return to the departure station. In the lapse of time it is possible to observe the suggestive panorama of the Lucanian Dolomites at a height of about 400 meters from the soil.

The two centers, Castelmezzano and Pietrapertosa are connected by the ‘Sentiero delle Sette Pietre’, one and a half hour naturalistic trek. A journey into fantasy and tradition but also the "Flight of the Angel" is very spectacular and takes place in the summer period (between June and September). Tied by a special harness and attached to a sturdy steel cable, this journey starts suspended in the air from Castelmezzano to arrive at Pietrapertosa (or vice versa) at a speed of about 120 km / h and the same procedure is repeated to return to the departure station. In the lapse of time it is possible to observe the suggestive panorama of the Lucanian Dolomites at a height of about 400 meters from the soil.