"From afar Bari has a magnificent effect. The city is defended by a double wall and an ancient castle; it stands on a rocky triangular peninsula of about a mile in circumference. The houses are generally very modest ... The walk on the new bastion behind the port it is the most pleasant; at each turn a different panorama of the sea and the coast opens up, from the cliffs of the Gargano to the hills of Ostuni ... ".

So wrote, at the end of the eighteenth century, the English traveler Henry Swinburne. Bari is the capital of Puglia and has about 320,000 inhabitants. The city develops on the coast of the Lower Adriatic and is one of the most active economic centers of Southern Italy, the main economic center of the entire region as well as for technological research. It is home to the annual "Fiera del Levante". Even the hasty visitor quickly notices that the city is made up of two distinct parts: on one side there is "Bari Vecchia", that includes the most important medieval and Renaissance monuments such as the Romanesque cathedral, dedicated to "San Sabino", the Romanesque basilica of "San Nicola", the Norman-Swabian castle of "Federico II", the church of "San Ferdinando", the "Fortino di Sant'Antonio Abate". It is the most characteristic part of Bari, composed of small alleys of rare beauty, panoramic views, ancient perfumes. The second part is the so-called "Bari Nuova", born in the early nineteenth century with an edict by Joachin Murat, and characterized by open, long and straight roads.

In reality, the soul of Bari, its "genius loci", comes from the sea whose infinite consequences has entailed the reality of this city. Called "Queen of Puglia", but also "Queen of the Adriatic", Bari has found its fortunes and misfortunes in the sea. The fortunes are summed up by its position as a gateway to East and in the intense maritime traffic - commercial and cultural - that have always characterized its activities. But the misfortunes also came from the sea: a thousand times Bari was attacked, plundered, impoverished by the incursions of the Saracen pirates. The Berbers came from the sea and conquered the city in 847 and dominated it for almost thirty years. Its position on the sea, dominating the lower Adriatic, attracted endless struggles for the occupation of this important outpost. After the long parenthesis of Rome, Bari was gradually conquered by the Lombards, the Byzantines, then by the Normans, the Swabians, the Angevins, the Aragonese, the Sforza, the Spaniards. Each of these civilizations has left indelible imprints in Bari, not only in architecture and construction, but also in the character of the inhabitants: industrious and trafficked, open to novelties and exchanges, curious and proud of their cosmopolitan past.

In reality, the soul of Bari, its "genius loci", comes from the sea whose infinite consequences has entailed the reality of this city. Called "Queen of Puglia", but also "Queen of the Adriatic", Bari has found its fortunes and misfortunes in the sea. The fortunes are summed up by its position as a gateway to East and in the intense maritime traffic - commercial and cultural - that have always characterized its activities. But the misfortunes also came from the sea: a thousand times Bari was attacked, plundered, impoverished by the incursions of the Saracen pirates. The Berbers came from the sea and conquered the city in 847 and dominated it for almost thirty years. Its position on the sea, dominating the lower Adriatic, attracted endless struggles for the occupation of this important outpost. After the long parenthesis of Rome, Bari was gradually conquered by the Lombards, the Byzantines, then by the Normans, the Swabians, the Angevins, the Aragonese, the Sforza, the Spaniards. Each of these civilizations has left indelible imprints in Bari, not only in architecture and construction, but also in the character of the inhabitants: industrious and trafficked, open to novelties and exchanges, curious and proud of their cosmopolitan past.

But there is more. The ongoing conquest, the constant danger of invasion and new subjection, have certainly favored the natural and genuine religious propensity of the people of Bari. Here then, in the 11th century, sixty-two Bari sailors went to Asia Minor and managed to steal and bring back to Bari the remains of San Nicola, bishop of Mira. The Baresi erected a stupendous Basilica to the holy thaumaturge, destination of pilgrimages, of faith and of a fervent and perpetual cult. In this regard, Italo Calvino wrote:«... The world around ancient "San Nicola" is an anthill drunk with vitality. Old courtyards are rooms, old chapels are warehouses, a staircase breaks through a wall, a wall raises its head beyond the ceiling. The seller of dried and salted tomatoes passes with his arm outstretched and his incomprehensible lament excites the appetite. Then a thousand half-naked children stick out their piece of bread. While the mother combs the mistress, the daughter makes the dough on a large stone in front of the door. With a pinch of pasta she brings other puppets into the world, she blows up: go play, get out of here. In this way the old Bari is endlessly multiplied, thank God, it grows new and never dies ».

The love for trade and religious faith, however, do not go to the detriment of cultural demands: that’s why Bari is the city of Laterza publisher who popularized the works of the great Neapolitan philosopher Benedetto Croce in the early twentieth century. On the contrary, the Bari merchant, who works night and day to sell his goods, has the dream of having his son lawyer or engineer, notary or doctor; in short, far from the often uncertain life of people linked to commerce. This justifies the role of the University of Bari which, with its student population of around 45,000, is one of the most crowded in Italy.

Here the hopes of the young people of Bari, their peers from Basilicata, Calabria, Molise, and the numerous Greek and Third World students are born. Hopes often destined to break against a reality made of unemployment or underemployment. The employment problem, then, is particularly dramatic in a city which, like Bari, has a shortage of large industries, even if the province's economy seems to be heading towards intense industrial development.

Here the hopes of the young people of Bari, their peers from Basilicata, Calabria, Molise, and the numerous Greek and Third World students are born. Hopes often destined to break against a reality made of unemployment or underemployment. The employment problem, then, is particularly dramatic in a city which, like Bari, has a shortage of large industries, even if the province's economy seems to be heading towards intense industrial development.

The overall picture is characterized - north of Bari - by the presence of large inhabited centers and, especially in the interior, by sparsely inhabited countryside in which they are scattered, to mark the boundaries of crops and properties, white stone drybwalls and "masserie" which are suggestive examples of spontaneous architecture. In addition to the romantic walks on the seaside, where you are taken by the charm of Bari and the Mediterranean waters that bathe it, the city is famous for its simple and tasty cuisine: excellent fish soups, seafood, vegetables and typical dishes like the "ncapriata", the lamb cooked in different ways, the famous orecchiette, the homemade tagliatelle, the "aubergine", all seasoned with the excellent olive oil produced nearby.

Excavations of 1913 ascertained the presence of a Bronze Age village and Peucetian culture later, in the most extreme tip of the old city, as if it already indicated to future generations the close relationship that the city of Bari would have had with the sea . The first reliable and documented data about the history of the city, refer to the Roman conquest, which occurred in the third century BC. During the long Roman domination, Bari established itself as a fishing port and trade center: it became municipium cum suffragium, with the possibility of issuing its own laws and having its own institutions, while depending on Rome. The city was located along Via Traiana, of which some milestones remain. Bari owned a mint and had a Pantheon, dedicated to its pagan deities. With the fall of Rome (476 AD), Bari passed under the dominion of the Ostrogoths and later of the Longobards. In 847, in the midst of Arab expansion in the Mediterranean, the Arabs took advantage of the weakness of the Longobard princes engaged in fratricidal struggles, and conquered Bari and its hinterland by declaring the foundation of the Emirate of Bari.

Excavations of 1913 ascertained the presence of a Bronze Age village and Peucetian culture later, in the most extreme tip of the old city, as if it already indicated to future generations the close relationship that the city of Bari would have had with the sea . The first reliable and documented data about the history of the city, refer to the Roman conquest, which occurred in the third century BC. During the long Roman domination, Bari established itself as a fishing port and trade center: it became municipium cum suffragium, with the possibility of issuing its own laws and having its own institutions, while depending on Rome. The city was located along Via Traiana, of which some milestones remain. Bari owned a mint and had a Pantheon, dedicated to its pagan deities. With the fall of Rome (476 AD), Bari passed under the dominion of the Ostrogoths and later of the Longobards. In 847, in the midst of Arab expansion in the Mediterranean, the Arabs took advantage of the weakness of the Longobard princes engaged in fratricidal struggles, and conquered Bari and its hinterland by declaring the foundation of the Emirate of Bari.

The emirs forbade the continuation of the use of churches and built a large mosque in Bari. Other than that, they guaranteed a certain religious tolerance in the city. Arab domination ended in 871, then 24 years after their establishment. The joint forces of the Byzantines and the Franks conquered the city after 3 years of siege and Bizantium took advantage of the void left by the Longobards of Benevento and took possession of it.

The emirs forbade the continuation of the use of churches and built a large mosque in Bari. Other than that, they guaranteed a certain religious tolerance in the city. Arab domination ended in 871, then 24 years after their establishment. The joint forces of the Byzantines and the Franks conquered the city after 3 years of siege and Bizantium took advantage of the void left by the Longobards of Benevento and took possession of it.

The transition from Longobard to Arab and then Byzantine power brought about significant changes. Bari became a city dominated by Byzantium, consolidating that character - which it has no longer lost - of a city-bridge between East and West, in other words a frontier city. Bari therefore became the largest Italian political, military and commercial center of the Eastern Empire, as well as the seat of the "Catapano", Greek commander who governed all the territories of Byzantium in the West. A period of prosperity and expansion opened up for the city. Around the year 1000 the city suffered tremendous assaults by Saracen pirates. The most serious of these, in 1001, continued in a long siege: the city was saved by the intervention of the Venetian fleet, under the command of the doge Pietro Orseolo II. Led by Melo da Bari, the Baresi rebelled against Byzantine power, but were defeated in 1018. The Byzantine domination ended in 1071, when the Norman Robert the Guiscard conquered the city.

Under the Norman domination, the port of Bari became very famous, as one of the main embarkation ports for the Crusades. In fact, in 1096, after the preaching of Peter the Hermit, warriors from all over Europe flocked to Bari to go to the first Crusade. In that time, the most significant events for Bari were: the birth of the Municipality, the construction of the basilica of San Nicola and its consecration by Urban II. Being very close to Byzantium economically and culturally fuelled several revolts with the worst ended in 1156, when William I, known as Malo, stormed the city and destroyed it, sparing only the Basilica of San Nicola. The city was rebuilt by Frederick II of Swabia who spent one of its most splendid periods in Bari. The enlightened ruler gave new impetus to port and industrial activities, restored the Castle and made the arts and culture flourish in his court. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries with the Angevins, the situation changed again.

Under the Norman domination, the port of Bari became very famous, as one of the main embarkation ports for the Crusades. In fact, in 1096, after the preaching of Peter the Hermit, warriors from all over Europe flocked to Bari to go to the first Crusade. In that time, the most significant events for Bari were: the birth of the Municipality, the construction of the basilica of San Nicola and its consecration by Urban II. Being very close to Byzantium economically and culturally fuelled several revolts with the worst ended in 1156, when William I, known as Malo, stormed the city and destroyed it, sparing only the Basilica of San Nicola. The city was rebuilt by Frederick II of Swabia who spent one of its most splendid periods in Bari. The enlightened ruler gave new impetus to port and industrial activities, restored the Castle and made the arts and culture flourish in his court. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries with the Angevins, the situation changed again.

The city was prostrated by the harsh taxation of Charles I of Anjou and his successors. Bari declined to the point that in the fifteenth century it was subjected to the feudal domination of the princes of Taranto and then of the Dukes of Milan, the Sforza.

With Isabella of Aragon, who had arrived in Bari in 1501, the sixteenth century was characterized by a period of considerable prosperity. Isabella was succeeded by her daughter Bona, who remained widow of Sigismondo l, king of Poland, moved to Bari, where she reigned with justice and wisdom: on her death, which occurred in 1557, the Baresi wanted to honor her, burying her in San Nicola. Bari became part of the Kingdom of Naples, which had passed under Spanish influence since 1503, ruled by a viceroy. The age of the viceroyalty was unhappy for the South: abuses, bullying, violence, robberies, assassinations, harsh taxes. An attempted riot by the Baresi, led by Paolo Ribecco, ended in mourning and ruins. To aggravate the situation there were two terrible plague epidemics in the city, one in 1656 and one in 1691.

With Isabella of Aragon, who had arrived in Bari in 1501, the sixteenth century was characterized by a period of considerable prosperity. Isabella was succeeded by her daughter Bona, who remained widow of Sigismondo l, king of Poland, moved to Bari, where she reigned with justice and wisdom: on her death, which occurred in 1557, the Baresi wanted to honor her, burying her in San Nicola. Bari became part of the Kingdom of Naples, which had passed under Spanish influence since 1503, ruled by a viceroy. The age of the viceroyalty was unhappy for the South: abuses, bullying, violence, robberies, assassinations, harsh taxes. An attempted riot by the Baresi, led by Paolo Ribecco, ended in mourning and ruins. To aggravate the situation there were two terrible plague epidemics in the city, one in 1656 and one in 1691.

With the Spanish succession war, the Neapolitan passed to Austria under the emperor Charles VI. In 1734, with the Polish succession war, Charles III of Bourbon took the Neapolitan from Charles VI; legitimized with the peace of Wien in 1738. Charles III is considered an enlightened king, and the city of Bari benefited greatly from his rule. In 1759, he left the crown to his brother Ferdinando VI, to take over the Spanish one. For the city of Bari, the eighteenth century was a period of continuous contrasts between the nobility and the clergy, rich in privileges, and the active and enterprising bourgeoisie. The French revolution had no repercussions in the South, but new ideas brought about very important events. In 1798, a revolutionary government was formed. In 1806, Emperor Napoleon declared the Bourbons fallen, occupied the South and placed his brother Giuseppe on the throne, who gave way to his brother-in-law Joaquin Murat to take over the Spanish crown. In 1808 Murat proclaimed Bari the capital and started building the new town. After his death (1815), Bari was ruled by the Bourbon rulers Ferdinando I, Ferdinando II and Francesco II, until national unification (1860).

The Basilica of San Nicola was built between 1087 and 1097 to guard the mortal remains of San Nicola, that in 1087 sixty-two Bari sailors had managed to steal in Mira, Licia, and to transport them to Italy. When the relics arrived in Bari, the abbot Elia - who later became bishop of the city - began building a new church. The construction was rapid, and in 1089 Urban II consecrated the crypt and deposited the relics there: in October of the same year, he held a council against the Greek church. The Basilica was so important, and the Saint so revered, that even William the Malo spared the building from the general destruction perpetrated in 1156.

The Basilica of San Nicola was built between 1087 and 1097 to guard the mortal remains of San Nicola, that in 1087 sixty-two Bari sailors had managed to steal in Mira, Licia, and to transport them to Italy. When the relics arrived in Bari, the abbot Elia - who later became bishop of the city - began building a new church. The construction was rapid, and in 1089 Urban II consecrated the crypt and deposited the relics there: in October of the same year, he held a council against the Greek church. The Basilica was so important, and the Saint so revered, that even William the Malo spared the building from the general destruction perpetrated in 1156.

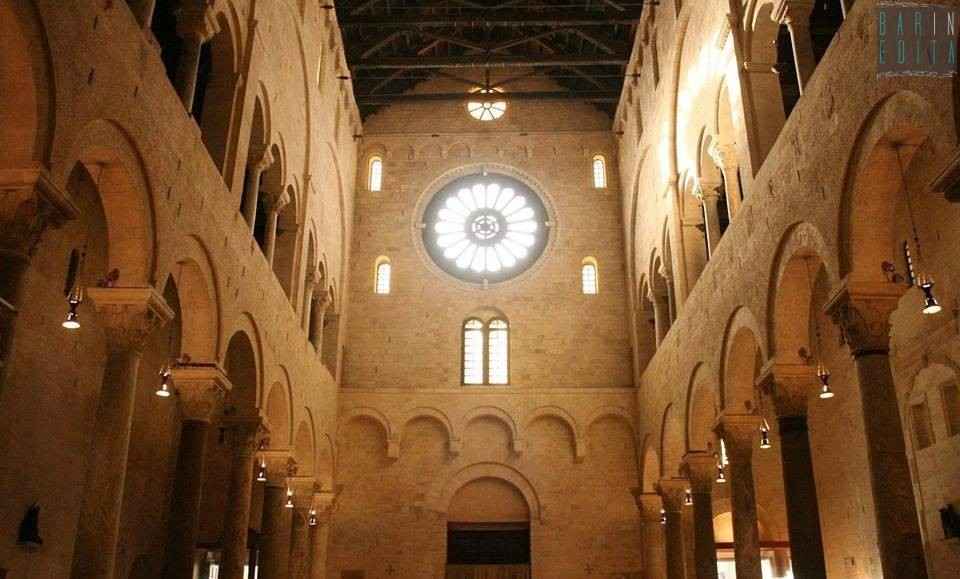

At the miraculous temple, besides the crowds of believers, popes and sovereigns also came in an act of faith. From this basilica, Pietro the Hermit launched his passionate appeal for the liberation of the Holy Sepulcher; here Roger the Norman, Arrigo VI, the empress Constance and the pale Manfred were crowned kings. The imposing walls, the tripartite facade with the arches at the top, the mullioned windows, the massive transept, the three naves divided by columns and pillars, the triforium matroneums, are all characteristic elements of the Romanesque style.

The façade is simple but majestic, flanked by two severed bell towers. Tripartite by pilasters, it is crowned by arches and open at the top by mullioned windows and at the bottom by three portals: of these, the median is canopied on columns, and richly carved. The sides with deep blind arches and rich doors are admirable. Blind arches at the bottom and mullioned windows at the top animate the high heads of the transept and the continuous apse wall, decorated in the center by a large window.

The façade is simple but majestic, flanked by two severed bell towers. Tripartite by pilasters, it is crowned by arches and open at the top by mullioned windows and at the bottom by three portals: of these, the median is canopied on columns, and richly carved. The sides with deep blind arches and rich doors are admirable. Blind arches at the bottom and mullioned windows at the top animate the high heads of the transept and the continuous apse wall, decorated in the center by a large window.

The majestic interior has three naves, divided by columns and pillars, with a large transept and three apses. Above the arches is the floor of the triforium matroneum. The carved and gilded ceiling is characterized by 17th century painted panels. The high altar is surmounted by a XII century ciborium, the oldest in Puglia. In the central apse worthy of note are: the floor with marble inlays and oriental motifs from the first decades of the XII century; the beautiful episcopal chair of 1105, called "chair of Abbot Elia", a large marble throne carved from a single block, which is located behind the ciborium; the sixteenth-century funeral monument of Bona Sforza. The altar in the right apse features a fifteenth-century triptych by A. Rico da Candia; in the rear wall there are remains of fourteenth-century frescoes. On the right stands the rich altar of San Nicola, in embossed silver foil, from 1684. In the left apse, a panel with Madonna and Saints from 1476 stands out.

The majestic interior has three naves, divided by columns and pillars, with a large transept and three apses. Above the arches is the floor of the triforium matroneum. The carved and gilded ceiling is characterized by 17th century painted panels. The high altar is surmounted by a XII century ciborium, the oldest in Puglia. In the central apse worthy of note are: the floor with marble inlays and oriental motifs from the first decades of the XII century; the beautiful episcopal chair of 1105, called "chair of Abbot Elia", a large marble throne carved from a single block, which is located behind the ciborium; the sixteenth-century funeral monument of Bona Sforza. The altar in the right apse features a fifteenth-century triptych by A. Rico da Candia; in the rear wall there are remains of fourteenth-century frescoes. On the right stands the rich altar of San Nicola, in embossed silver foil, from 1684. In the left apse, a panel with Madonna and Saints from 1476 stands out.

At the end of the aisles, one of the stairs leads down to the Crypt, as large as the transept: it has three apses and is supported by 26 columns embellished with Romanesque capitals. Under the altar of the crypt lie the remains of San Nicola. From the bones of the saint, patron of the city, the monks would have extracted a liquid with miraculous powers, called "manna". That is why qualities of thaumaturge are attributed to St. Nicholas.

At the end of the aisles, one of the stairs leads down to the Crypt, as large as the transept: it has three apses and is supported by 26 columns embellished with Romanesque capitals. Under the altar of the crypt lie the remains of San Nicola. From the bones of the saint, patron of the city, the monks would have extracted a liquid with miraculous powers, called "manna". That is why qualities of thaumaturge are attributed to St. Nicholas.

The museum, ordered in the right nave, presents the surviving pieces of the so-called Treasure of San Nicola (reliquaries, candlesticks, illuminated manuscripts), to which have been added paintings, furnishings, furnishings and above all sculptures, often fragmentary, found inside the towers or under the floors of the transept and of the crypt during recent restoration works.

The Cathedral of Bari, dedicated to "San Sabino", looks onto "Piazza dell'Odegitria" (Ogeditria’s Square) and it is considered the most beautiful Apulian architectural monument of the thirteenth century. In reality, what we see is neither the ancient cathedral built in the first thirty years of the eleventh century under the Archbishop of Byzantium, nor the first one - partially or totally destroyed - that was built between 1171 and 1188 and consecrated in 1292. The opinions of historians disagree about the fate of the first construction of the Cathedral; if it was completely destroyed together with the rest of the city in 1156 by William the Malo, or if something of it, among the general ruin, was spared.

The Cathedral of Bari, dedicated to "San Sabino", looks onto "Piazza dell'Odegitria" (Ogeditria’s Square) and it is considered the most beautiful Apulian architectural monument of the thirteenth century. In reality, what we see is neither the ancient cathedral built in the first thirty years of the eleventh century under the Archbishop of Byzantium, nor the first one - partially or totally destroyed - that was built between 1171 and 1188 and consecrated in 1292. The opinions of historians disagree about the fate of the first construction of the Cathedral; if it was completely destroyed together with the rest of the city in 1156 by William the Malo, or if something of it, among the general ruin, was spared.

Nevertheless the second building, made or not on the same ground, and with the same arches, was disfigured by the clumsy eighteenth-century architecture and even more by the baroque disfigurements - carried out in 1741 by Archbishop Gaeta and the architect Domenico Vaccaro - who modified the facade, the interior of the naves, the interior of the Trulla and the Crypt. Restoration work carried out in the mid-twentieth century restored the medieval facade of the temple. In particular, the internal furnishings were brought back to the ancient Romanesque features, creating the ciborium, the ambo and the presbytery fence. On the colonnades and arches of the central nave were opened the three-light windows of the matroneums never used and replaced with hanging balconies. The Cathedral, in Romanesque style, preserves one of the two original bell towers (the second collapsed in 1613) and has an octagonal drum dome. The beautiful main facade is sloping, finished in a spire and divided into three by pilasters, according to the internal order of the naves. It has remained whole only in the upper part, where you can admire the internal cornice and the face below, adorned with beautiful bas-reliefs of leaves and flowers with branched excerpt. The large central rose window, despite the damage suffered in the interior, retains its rosary crown frame with an overlying semicircular palmette frame, on which sphinx and various animal figurines protrude. On the rear facade stands the magnificent window.

Nevertheless the second building, made or not on the same ground, and with the same arches, was disfigured by the clumsy eighteenth-century architecture and even more by the baroque disfigurements - carried out in 1741 by Archbishop Gaeta and the architect Domenico Vaccaro - who modified the facade, the interior of the naves, the interior of the Trulla and the Crypt. Restoration work carried out in the mid-twentieth century restored the medieval facade of the temple. In particular, the internal furnishings were brought back to the ancient Romanesque features, creating the ciborium, the ambo and the presbytery fence. On the colonnades and arches of the central nave were opened the three-light windows of the matroneums never used and replaced with hanging balconies. The Cathedral, in Romanesque style, preserves one of the two original bell towers (the second collapsed in 1613) and has an octagonal drum dome. The beautiful main facade is sloping, finished in a spire and divided into three by pilasters, according to the internal order of the naves. It has remained whole only in the upper part, where you can admire the internal cornice and the face below, adorned with beautiful bas-reliefs of leaves and flowers with branched excerpt. The large central rose window, despite the damage suffered in the interior, retains its rosary crown frame with an overlying semicircular palmette frame, on which sphinx and various animal figurines protrude. On the rear facade stands the magnificent window.

The solemn and harmonious interior has three naves and three apses. There are fake matroneums and the stylophorum lions at the entrance of the presbytery, as well as the episcopal chair, the pulpit and the ciborium. The marble furnishings and the decoration of all the architectural parts, attributed to great sculptors such as Alfano da Termoli, Anseremo da Trani, Peregrino da Salerno, are very rich. The fresco wall decoration is also rich, of which some remains in the minor apses and in the crypt survive. With the recovery of the twentieth century, each artistic object was restored and re-proposed to the reading of scholars and visitors, to recompose the image of one of the most beautiful churches of all southern Italy.From the left nave you enter an ancient baptistery, called Trulla, transformed into a sacristy and to the Crypt. The latter was restored in 1156, after the destruction wrought by William the Malo, and houses the remains of "San Sabino". Inside, you can admire beautiful fourteenth-century frescoes and the precious Byzantine icon of the Madonna of Constantinople, called Madonna Odegitria.

The solemn and harmonious interior has three naves and three apses. There are fake matroneums and the stylophorum lions at the entrance of the presbytery, as well as the episcopal chair, the pulpit and the ciborium. The marble furnishings and the decoration of all the architectural parts, attributed to great sculptors such as Alfano da Termoli, Anseremo da Trani, Peregrino da Salerno, are very rich. The fresco wall decoration is also rich, of which some remains in the minor apses and in the crypt survive. With the recovery of the twentieth century, each artistic object was restored and re-proposed to the reading of scholars and visitors, to recompose the image of one of the most beautiful churches of all southern Italy.From the left nave you enter an ancient baptistery, called Trulla, transformed into a sacristy and to the Crypt. The latter was restored in 1156, after the destruction wrought by William the Malo, and houses the remains of "San Sabino". Inside, you can admire beautiful fourteenth-century frescoes and the precious Byzantine icon of the Madonna of Constantinople, called Madonna Odegitria.

Bari Castle was built - around 1131 - on previous housing structures from Byzantine era. Roger the Norman wanted it, for evident defensive purposes. Little remains of the original structure because, in 1156, William the Malo attacked and destroyed the city. Some religious buildings were spared, but the castle was reduced to little more than a ruin. The current complex is the reconstruction of 1233-1240, due to the emperor Federico II, and the genius of the architect Guido del Vasto. During the Crusades, the castle was the usual shelter for knights leaving and arriving from the Holy Land. Between 1280 and 1463, it was entrusted to various feudal lords. In 1308, during the Kingdom of the Angevins, the Templars of Southern Italy were arrested and kept here, until 1312, when the Order was suppressed.

Bari Castle was built - around 1131 - on previous housing structures from Byzantine era. Roger the Norman wanted it, for evident defensive purposes. Little remains of the original structure because, in 1156, William the Malo attacked and destroyed the city. Some religious buildings were spared, but the castle was reduced to little more than a ruin. The current complex is the reconstruction of 1233-1240, due to the emperor Federico II, and the genius of the architect Guido del Vasto. During the Crusades, the castle was the usual shelter for knights leaving and arriving from the Holy Land. Between 1280 and 1463, it was entrusted to various feudal lords. In 1308, during the Kingdom of the Angevins, the Templars of Southern Italy were arrested and kept here, until 1312, when the Order was suppressed.

Subsequently the castle passed to Ferrante d'Aragona, when Bari became part of its royal domain. With the Aragonese, the building took on its current configuration, with four corner lance bastions. Subsequently, it was donated to the Sforza family, on the occasion of the wedding of Alfonso of Aragon with the daughter of the Duke of Milan. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, the manor became the home of the Duchess of Bari, Isabella of Aragon, who transformed the castle into a luxurious fortified residence, a destination for writers, artists and powerful court men. In particular, the complex was equipped by three sides facing the land by mighty ramparts, reinforced by powerful bulwarks: in addition, a large moat was built around the Castle. In the nineteenth century, the castle was used by the Bourbons as a fortress and prison; then it became an infantry barracks and gendarmerie.The mighty and grandiose construction is made up of two distinct parts: the first includes the donjon of Byzantine-Norman origin and transformed by Frederick II. The donjon has a trapezoidal plan, with two of the original four towers. The second part includes the escarpment ramparts with angular spear towers on the moat, which were added by Isabella of Aragon. The north side, the one on the sea, preserves the ogival portal (now walled) and the graceful mullioned windows of the thirteenth-century reconstruction.

Subsequently the castle passed to Ferrante d'Aragona, when Bari became part of its royal domain. With the Aragonese, the building took on its current configuration, with four corner lance bastions. Subsequently, it was donated to the Sforza family, on the occasion of the wedding of Alfonso of Aragon with the daughter of the Duke of Milan. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, the manor became the home of the Duchess of Bari, Isabella of Aragon, who transformed the castle into a luxurious fortified residence, a destination for writers, artists and powerful court men. In particular, the complex was equipped by three sides facing the land by mighty ramparts, reinforced by powerful bulwarks: in addition, a large moat was built around the Castle. In the nineteenth century, the castle was used by the Bourbons as a fortress and prison; then it became an infantry barracks and gendarmerie.The mighty and grandiose construction is made up of two distinct parts: the first includes the donjon of Byzantine-Norman origin and transformed by Frederick II. The donjon has a trapezoidal plan, with two of the original four towers. The second part includes the escarpment ramparts with angular spear towers on the moat, which were added by Isabella of Aragon. The north side, the one on the sea, preserves the ogival portal (now walled) and the graceful mullioned windows of the thirteenth-century reconstruction.

The castle is accessed from the south side, crossing the bridge over the moat and entering the courtyard between the sixteenth-century bulwarks and the Swabian donjon, whose towers and curtains were made of dark stone drafts, with several single-lancet windows. On the west side, a carved Gothic portal leads into an atrium over columns with cross vaults, from which you pass into the internal courtyard, quadrilateral, with a Renaissance layout, which has been much altered. In this interior, on the left in a hall on the ground floor is the town Gipsoteca. Next to it, an interesting room with a pointed barrel vaulted ceiling is used as an archive. On the upper floor, on the southern side of the castle, there is the Superintendency of Puglia's historical and artistic architectural heritage.

Piazza del Ferrarese is located in the area of one of the access gates to the medieval city, the so-called Porta di Mare, or Porta Australe, or Porta di Lecce, opened in 1612 to facilitate the entry of goods into the nearby Mercantile square where it was held the market. The work was accomplished under the reign of Philip III of Spain. A couplet and an inscription praising the king were carved on the gate. Finally the effigies of Japige and Barione, the mythical founders of Bari were engraved above the gate.

Piazza del Ferrarese is located in the area of one of the access gates to the medieval city, the so-called Porta di Mare, or Porta Australe, or Porta di Lecce, opened in 1612 to facilitate the entry of goods into the nearby Mercantile square where it was held the market. The work was accomplished under the reign of Philip III of Spain. A couplet and an inscription praising the king were carved on the gate. Finally the effigies of Japige and Barione, the mythical founders of Bari were engraved above the gate.

Piazza del Ferrarese is important because it has brought to light a section of the ancient Via Appia-Traiana, built by the Romans at the beginning of the second century AD. The square takes its name from a merchant from Ferrara - such as Stefano Fabri or Fabbro - who settled in Bari in the seventeenth century and kept his warehouse here. This merchant left a good memory of himself, having financed the construction of the upper loggia of the Palazzo del Sedile.

The Column of Justice stands next to the Palazzo del Sedile, on the left side of Piazza Mercantile. Called by the Baresi "infamous column", it was actually the structure where insolvent debtors and bankrupted ones were chained and exposed to the public, in short, it was the pillory of the city. According to some scholars, the column was erected in the mid-sixteenth century, by the will of the Spanish viceroy Pietro di Toledo, who issued a decree to make less harsh the sedan's sentence. The artifact consists of a column of white marble, surmounted by a sphere, and a stone lion, of natural proportions, which crouches at the base. It bears a collar on the chest engraved with the writing Custos Iusticiae, or keeper of justice. It appears that the condemned were placed astride this animal, with their buttocks exposed and their hands chained to the column.

The Column of Justice stands next to the Palazzo del Sedile, on the left side of Piazza Mercantile. Called by the Baresi "infamous column", it was actually the structure where insolvent debtors and bankrupted ones were chained and exposed to the public, in short, it was the pillory of the city. According to some scholars, the column was erected in the mid-sixteenth century, by the will of the Spanish viceroy Pietro di Toledo, who issued a decree to make less harsh the sedan's sentence. The artifact consists of a column of white marble, surmounted by a sphere, and a stone lion, of natural proportions, which crouches at the base. It bears a collar on the chest engraved with the writing Custos Iusticiae, or keeper of justice. It appears that the condemned were placed astride this animal, with their buttocks exposed and their hands chained to the column.